Rate rise reality check: Mortgage jumps don't slow spending

Research reveals that Australian mortgage holders maintained spending by using savings buffers, despite interest rate rises

At the start of 2022, there were notable increases in central bank interest rates across many developed countries. Australian households with variable-rate mortgages absorbed massive increases in loan repayments without cutting their spending, according to groundbreaking research that tracked real banking data through the sharpest interest rate rises in decades.

The study, conducted by researchers from the e61 Institute, University of Sydney, University of Chicago and UNSW Sydney, found that variable-rate mortgage holders maintained their consumption patterns despite monthly repayments increasing by around $1000 between mid-2022 and early 2024. The Reserve Bank of Australia raised the cash rate from 0.1% to 4.35% during this period, representing a cumulative 425 basis point increase.

Despite the large increase in required mortgage repayments, the research found that relative spending for the two groups remained little changed until at least early 2024 (when comparing mortgage holders to non-mortgage holders). The findings challenge the widely held belief that economies with high proportions of variable-rate debt experience more immediate monetary policy impacts on household spending.

Australia has among the highest shares of variable-rate mortgage debt globally, with these loans historically accounting for 85% of new lending. Australia provides an ideal setting to study the transmission of monetary policy to household consumption, according to the research paper, which noted that the pass-through of changes in the central bank’s policy rate onto variable mortgage rates is rapid, with interest rate changes typically passed on within two weeks.

“2022 saw the most synchronised increase in interest rates across developed countries over the past 50 years,” said Dr Nalini Prasad, research co-author and Senior Lecturer in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School. “These interest rate increases were designed to reduce inflation through restraining household spending. It is thought that monetary policy is more powerful in countries with more variable rate mortgage debt, like Australia. Here, changes in interest rates lead to immediate changes in mortgage repayments. However, we show that when mortgagors have accumulated savings, spending does not need to fall after interest rates rise.”

Liquid mortgage features enable consumption smoothing

The research paper, The Mortgage Debt Channel of Monetary Policy When Mortgages are Liquid, was co-authored by Dr Prasad, Professor Greg Kaplan from the University of Chicago and e61 Institute, Dr Christian Gillitzer from the University of Sydney and Matthew Elias and Dr Gianna La Cava from the e61 Institute.

It reveals that Australian mortgage holders drew down accumulated savings buffers to maintain their spending levels rather than reducing consumption. Variable-rate mortgage holders experienced a $13,800 increase in repayments relative to fixed-rate mortgage holders over the 18-month period following interest rate rises, yet showed little difference in spending patterns.

“Over this period, variable-mortgagors experienced a $13,884 increase in mortgage repayments relative to fixed-rate mortgagors. There was little difference in the spending and incomes between fixed and variable-rate mortgagors,” the study found. The analysis showed that 70% of the increase in mortgage repayments was paid for by individual’s drawing down on their savings and 26% by individuals bringing in funds from external sources.

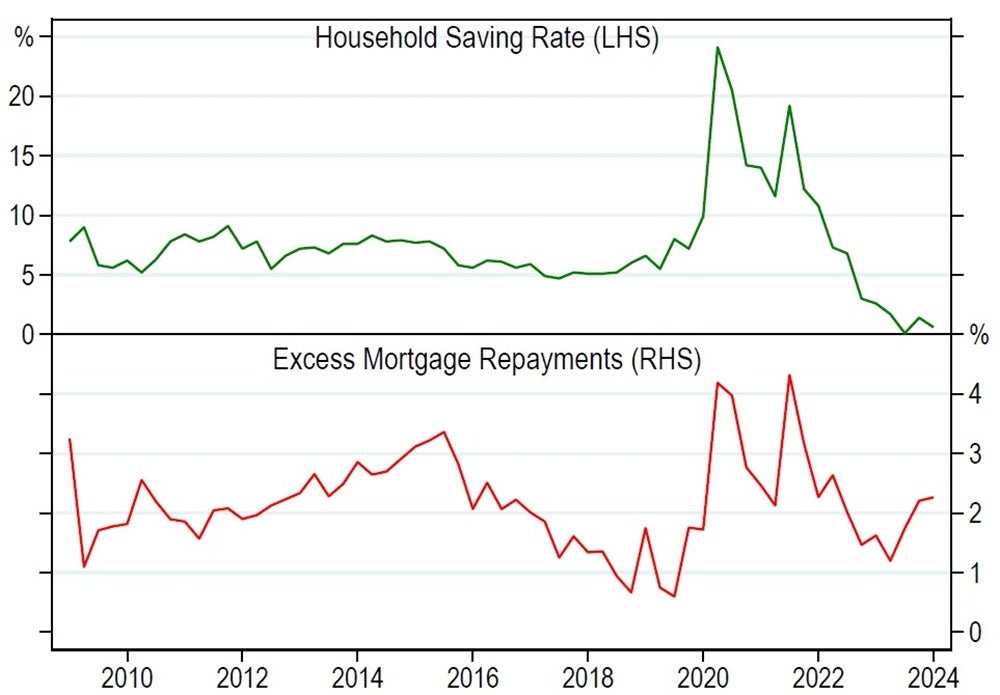

Household saving ratio and excess mortgage repayments

This consumption smoothing occurred because Australian variable-rate mortgages function as highly liquid assets through features like redraw facilities and offset accounts. An important feature of variable rate mortgages is that they provide a vehicle through which households can accumulate liquid wealth, so households can make mortgage repayments in excess of the required minimum, without incurring any service costs.

The study emphasised that any excess mortgage repayments can be taken off the mortgage in the future, for example to fund consumption. This feature is known as “redraw”. The researchers noted that it takes one day for an individual to withdraw excess repayments from their redraw account and convert it into cash.

The research methodology utilised de-identified bank transaction data from a major Australian bank, covering 83,321 individuals from November 2020 to April 2024. The researchers employed an event study framework comparing variable-rate and fixed-rate mortgage holders, with spending measured from transaction account flows following established academic approaches.

Pandemic savings provided cushion against rate rises

The timing of interest rate increases proved crucial, as they occurred after households had accumulated unprecedented savings during pandemic lockdowns. Average repayment buffers have been large and increased substantially during the pandemic, according to the study, which noted that, in the five years prior to the pandemic, aggregate excess repayments averaged 26% of required repayments but rose to 42% of required repayments in 2020-2021.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

The researchers found that excess repayments were made on 70% of variable-rate mortgage borrowers prior to the first rise in interest rates. Around a quarter of variable-rate mortgages had repayments in excess of 40% of required repayments. However, the study concluded that the share of variable-rate mortgages with excess repayments declined to around 25%.

The household saving ratio averaged 20% over the 2020-2021 pandemic years, compared with 7.7% in 2019. This provided substantial buffers for mortgage holders to draw upon when interest rates began rising.

Institutional features matter more than interest rate exposure

The findings highlight how mortgage market design influences monetary policy effectiveness beyond simple measures of variable-rate debt exposure. The researchers explained that redraw and offset accounts provide a cost-effective place for households to place their savings as it allows them to offset the interest expense on their mortgage (and any interest saving is not taxed).

“Consumption is sensitive to cash flows when high-return assets are illiquid, which is not the case for mortgagors in Australia,” the researchers explained. Variable-rate mortgage holders could access excess repayments through redraw facilities within days, while offset accounts provided immediate access to funds.

The study compared outcomes across different mortgage types, including combination mortgages with both fixed and variable components. Results remained consistent across various model specifications and robustness checks, including controls for selection effects and regional variations.

“We find little change in non-durable, durable and services spending for variable rate mortgagors relative to fixed rate mortgagors,” the analysis revealed. The research also examined fixed-rate mortgage expiries, where loans reset to variable rates with substantially higher payments, finding similar patterns of consumption smoothing.

Policy implications for monetary transmission

These findings carry significant implications for central bank policy and economic forecasting. “Even in a country with a high share of variable rate mortgages, where the transmission from interest rates to required repayments is large and immediate, the effect on spending through increased required repayments need not be large,” the study emphasised.

“Increases in interest rates reduce available cash flows for variable-rate mortgagors,” explained Dr Prasad. “But this doesn’t always translate into a slowing in spending. If spending does not slow, then this suggests that to reduce inflation, a central bank will need to push more strongly on the monetary policy lever.”

Learn more: Are you paying more interest on your mortgage than you think?

The researchers concluded that institutional features that make mortgages liquid “matter a lot”. Because the level of savings held on mortgages varies over time, the study found that the effect of monetary policy on spending is state-dependent.

“Our findings provide a cautionary tale,” the study warned, noting that monetary policy transmission through mortgage repayments may be weaker than commonly assumed, particularly when households hold substantial liquid savings buffers.