How the RBA could impact your mortgage, rent and savings in 2026

UNSW economists explain how Reserve Bank cash rate decisions respond to inflation and what this means for mortgages, rents, savings and spending

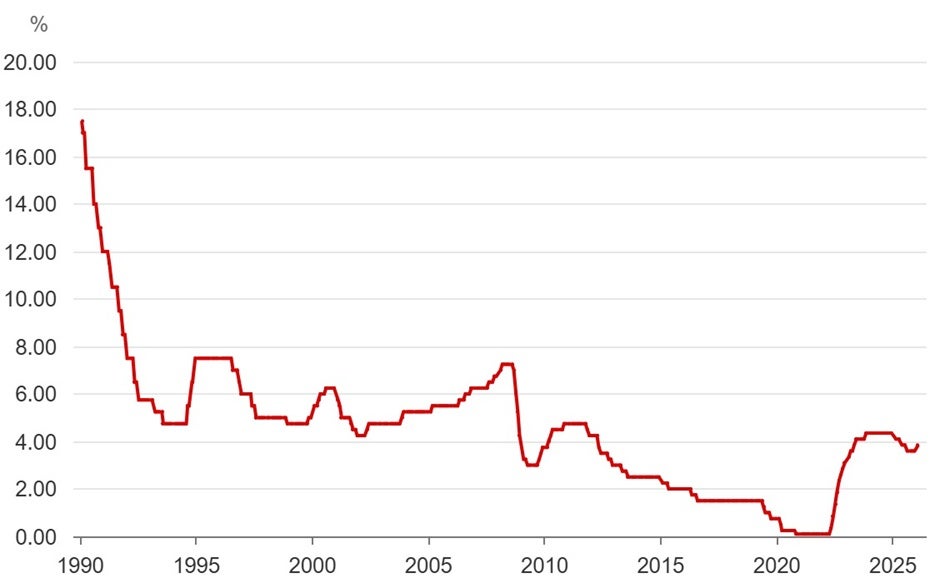

After several interest rate cuts last year, many Australians are looking ahead and asking whether further relief is on the way.

Australia is moving out of a period of high inflation, but price pressures have been more persistent than expected, leaving the Reserve Bank cautious about further rate cuts.

“Inflation has come down, but it is not yet back within the target range and has proved more persistent than expected. That is why the RBA has been cautious about easing policy,” said Associate Professor Evgenia Dechter from UNSW Business School. “The implication is that the cash rate is likely to stay relatively high for longer.”

The cash rate currently sits at 3.85%, following a recent 0.25% increase.

While economic growth is modest and the labour market remains relatively strong, UNSW economists say the path to lower rates will depend on how inflation, wages and productivity evolve.

Understanding how those decisions are made and which signals to watch can help Australians prepare for what this outlook could mean for mortgages, rents, savings, and spending.

What is the cash rate and why does it matter?

The cash rate is the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) main tool for steering the economy, and it shapes how much Australians pay to borrow and how much they earn on their savings.

“The cash rate is the interest rate set by the RBA that influences how much it costs to borrow money and how much you earn on your savings,” said Dr Nalini Prasad, Senior Lecturer in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School.

Changes to the cash rate flow through to household finances quickly. When rates rise, loan repayments increase and borrowing becomes more expensive. When rates fall, repayments ease, freeing up cash for other spending.

“A higher interest rate leads to higher costs for borrowers as interest rates on loans rise, leading to higher loan repayments,” Dr Prasad said. “It is beneficial for savers as the interest rates on their savings rise.”

By encouraging households and businesses to adjust how much they borrow or save, the RBA uses interest rates to influence inflation and employment across the economy. “Through changing the amount that consumers and businesses save and borrow, the RBA attempts to influence prices and employment in the economy,” Dr Prasad said.

Where cash rates could head next

According to UNSW experts, inflation, a general increase in prices and a fall in the purchasing value of money, will be the central factor shaping cash rate decisions as the Reserve Bank looks ahead through 2026.

“Inflation has not fallen as quickly as expected, and consumer spending remains resilient in the face of higher inflation. Inflation has been above the RBA’s target since the middle of 2025,” Dr Prasad said.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

If inflation pressures fail to ease further, interest rates may not fall as soon as many expect. “If inflation pressures persist, expect to see increases in the cash rate in 2026,” Dr Prasad said.

Dr Gonzalo Castex, Senior Lecturer in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School, said RBA decisions will depend on how inflation, wages and productivity evolve, as well as global economic conditions.

“In a favourable scenario, inflation returns sustainably to target, productivity improves, and wage growth moderates, allowing interest rates to gradually normalise,” Dr Castex said.

But risks remain tilted toward caution. “In a less favourable scenario, inflation could prove more persistent, driven primarily by stronger-than-expected wage pressures and, potentially, reinforced by renewed supply-side frictions, requiring policy to remain restrictive for longer.”

Taken together, these scenarios underscore why households should not expect a fixed path for interest rates. “Australians should understand that the RBA’s outlook is inherently uncertain and data dependent. Decisions will reflect a careful balance between controlling inflation and supporting employment, rather than a fixed path for interest rates,” he said.

That uncertainty also shapes expectations around the timing of any rate cuts. “The most realistic scenario is rates stay on hold for longer, with any easing likely to be gradual,” said A/Prof. Dechter.

“The cash rate could increase if inflation remains above the target range or accelerates, particularly if demand and the labour market remain stronger than expected,” she said.

What this could mean for mortgages, renters and savers

If interest rates stay higher for longer, the effects will be felt differently across households, depending on whether Australians are paying off a mortgage, renting, or relying on savings.

For mortgage holders, the outlook suggests repayments are likely to remain tight, even if rates eventually begin to ease. “For mortgage holders, the ‘higher for longer’ scenario means repayments stay high for a while, and relief would likely be gradual rather than immediate,” said A/Prof. Dechter.

Learn more: Rate rise reality check: Mortgage jumps don't slow spending

Even when the cash rate starts to fall, changes may take time to flow through to household budgets. “Rate cuts don't affect everyone at the same time. Mortgage holders may see some relief relatively quickly, while the broader effects on business conditions and the labour market take longer to emerge,” she said.

Renters may continue to face pressure regardless of short-term interest rate movements, as conditions in the rental market matter more than changes to the cash rate.

“Rental prices are primarily driven by supply and demand in the rental market. But when financing costs are high and vacancy rates are low, landlords may have greater opportunities to pass through those costs to renters. And over time, higher interest rates can also reduce new housing construction and future housing supply,” A/Prof. Dechter said.

On the other hand, higher interest rates can be a positive and can tend to benefit savers, with returns on savings remaining elevated while rates stay high. “A higher interest rate is beneficial for savers as the interest rates on their savings rise,” Dr Prasad said.

Those gains, however, sit alongside broader cost-of-living pressures, particularly if inflation remains elevated.

Preparing for what comes next

As the Reserve Bank weighs its next moves, the message for Australians is that any change is likely to be gradual rather than dramatic. Even as inflation moves back toward the Reserve Bank’s target range, many households may continue to feel financial pressure.

“It is also worth noting that even when inflation is back in the target range, it does not mean the cost of living falls; prices stay high, and wages can take time to catch up, so many households may still feel stretched,” said Dr Prasad.

“If inflation eases, the cash rate should eventually come down, and mortgage repayments will ease too, but we are unlikely to return to the ultra-low pandemic era rates.”

Global uncertainty adds another layer of complexity, underscoring the need for flexible policy settings. “Global uncertainty remains a risk, so the RBA will want to stay flexible, and Australians should be ready for policy to shift if external conditions change,” A/Prof. Dechter said.

That flexibility is central to how the Reserve Bank operates. “The RBA’s approach is forward-looking, meaning policy will adjust as new information emerges about the economy, both domestically and internationally,” Dr Castex concluded.